Donald Trump was angry: A reporter had the gall to suggest that ego was behind his purchase of New York’s famed Plaza Hotel.

When he thought about it, though, he decided it was true — and admitted as much in a big, big way.

“Almost every deal I have ever done has been at least partly for my ego,” the billionaire declared in a 1995 New York Times piece titled, “What My Ego Wants, My Ego Gets.”

Flash forward two decades, and what 70-year-old Donald John Trump wants is the presidency. To understand why, consider the billionaire’s ego not just as mere mortals might see it (an outsized allotment of conceit) but also as Trump himself understands it (an extraordinary drive for excitement, glamour and style that produces extraordinary success.)

As Trump once put it: “People need ego; whole nations need ego.”

The race for the White House, then, may be Trump’s ultimate ego trip, guided by the same instincts he’s relied on in a lifetime of audacious self-promotion, ambition and risk-taking.

Those instincts allowed a fabulously wealthy businessman to pull off a mind meld with the economic anxieties of ordinary Americans, elbowing aside the Republican A-team and breaking every rule of modern politics to become the party’s presumptive presidential nominee.

“I play to people’s fantasies,” Trump has acknowledged. And plenty of voters fantasize about bringing some of that Trump braggadocio to the American psyche.

Trump’s candidacy has given rise to a whole nation of armchair analysts with their own theories to explain the man: He’s a bully. He’s a champion. He’s insecure. He’s a rebel. He’s a narcissist. He’s an optimist. He’s calculating. He’s unscripted. He lacks self-awareness. He’s brimming with insight. He’s a pathological liar. He sees a larger truth.

Trump himself usually shies away from self-analysis. But he’s acknowledged that for much of his life, it’s been all about the chase: Whatever the game, he’s in it to win it.

“The same assets that excite me in the chase often, once they are acquired, leave me bored,” he told an interviewer in 1990, as his boom years were sliding toward bust. “For me, you see, the important thing is the getting, not the having.”

That mindset has generated plenty of speculation about whether Trump really wants to set aside his my-way lifestyle to shoulder the heavy demands of governing.

He bats away such talk. But his campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, has sketched out a limited level of presidential engagement for Trump in discussing a strong role for the candidate’s vice presidential choice.

“He needs an experienced person to do the part of the job he doesn’t want to do,” Manafort told The Huffington Post in May. He said Trump sees himself as chairman of the board, not the CEO and certainly not chief operating officer.

As a presidential candidate, Trump has a straightforward pitch.

“The country has been great to me and I want to give back,” he says. “And if people want me to do that, I think I’ll do a fantastic job for them.”

Not just fantastic. Perhaps even celestial.

“I will be the greatest jobs president that God ever created,” Trump said in his announcement speech.

Trump’s unbounded confidence — and obsession with winning — has been a lifelong constant, evident in ways small and large.

Growing up as one of five children in a well-to-do Queens real estate family, Donald was the brash one, a fighter from the start.

“We gotta calm him down,” his father would say, as Trump recalls it. “Son, take the lumps out.”

For good or ill, it’s advice Trump never really embraced.

Military school helped channel his energy, but Trump’s rebellious streak remained.

Trump followed his father into real estate, but chafed within the confines of Fred Trump’s realm in New York’s outer boroughs.

Manhattan’s skyline beckoned; He crossed the East River and never looked back.

“He’s gone way beyond me, absolutely,” an admiring Fred marveled. His son had made it big in Manhattan well before he hit 40.

So successful at such a young age, Trump never did have to smooth out those lumps his father had warned about.

“He was at the top of his own pyramid,” says Stanley Renshon, a political psychologist at the City University of New York who is writing a book about Trump. “Nobody was going to say, ‘Donald, tone it down.’ ”

Trump, who stresses his Ivy League education, revels in juvenile jabs, labeling his adversaries “stupid,” ”dumb” and “bad.”

“I know words,” he declared at a December campaign rally where he criticized the Obama administration. “I have the best words. But there’s no better word than stupid, right?”

With no one to shush or second-guess him, brashness has been Trump’s way, along with his trademark glitz and flash. (Flash, in Trump’s lexicon, registers a level below glitz.)

Through years of boom, bust and more than a decade of reality-TV celebrity on “The Apprentice,” the deals kept coming and the price tags (and, often, the debt) kept growing — as did the hype. Always the hype.

Telling snapshots:

— Trump, in a chance encounter with “Harry Potter” actor Daniel Radcliffe before they appeared on the “Today” show in 2005. Radcliffe, 16, told Trump he was nervous about making a live television appearance. Trump’s advice: “Just tell them you met Mr. Trump,” Radcliffe recalled in a recent appearance on “Late Night with Seth Meyers.”

“To this day,” said Radcliffe, “I can’t even relate to that level of confidence.”

— Trump, visiting Scotland in 2012 to fight the government’s proposed wind farm off the shore of his new golf resort there.

He was asked during a parliamentary inquiry to provide evidence for his claim that the “monstrous turbines” would hurt tourism.

“I am the evidence,” Trump answered in all seriousness, drawing laughter from the galleries. “I am a world-class expert in tourism.”

— Trump, chiming in with free advice for the Obama White House from the sidelines.

The businessman rang up Obama adviser David Axelrod in 2010 to volunteer to fix the BP spill that was gushing millions of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico and had confounded the world’s leading experts. Trump also brought up his disdain for the tent that the White House sometimes erects on the South Lawn for state dinners with world leaders. In his presidential campaign, Trump often tells of offering to build — and pay for — a “great, grand ballroom.”

Axelrod largely confirms Trump’s account — with one big exception.

“I honestly don’t recall him ever saying that he would pay for it,” says Axelrod. “That’s a line I would have remembered.”

He’s not all chutzpah.

Ivanka Trump tells of her “incredibly empathetic” father reaching out to help strangers he sees mentioned in the news whose stories of adversity touch him.

— A Mississippi man remembers Trump picking up the phone to call when the man’s father wrote to ask for a loan to build a hotel back in 1988. Trump didn’t offer a loan to the Indian-American small businessman, but did give him a pep talk and some advice.

“Trump inspired my father to the fullest when he told him that Dad’s immigrant story was wonderful,” Suresh Chawla wrote in a 2015 letter to The Clarksdale (Mississippi) Press Register.

— Pro golfer Natalie Gulbis tells of Trump encouraging her early in her career and coaching her on how to negotiate equal pay with male competitors.

Far more often, though, Americans have seen the tweet-storming settler of scores and hurler of insults — the man who takes every time-tested piece of conventional wisdom, does the opposite and somehow thrives.

For all the protesters who roil his rallies, Trump himself is the heckler of our time, who happens to do his jeering from the podium. No one is immune. Not senator and war hero John McCain, not the disabled, not Mexicans, not Muslims, not even those people who make up a majority of the country (and the electorate): women.

Vanquished rivals learned to their peril that to criticize Trump was to set off the nuclear option in response.

Trump calls it having a little fun.

Aubrey Immelman, a political psychologist at Saint John’s University in Minnesota who has developed a personality index to assess presidential candidates, puts Trump’s level of narcissism in the “exploitative” range, surpassing any presidential nominee’s score in the past two decades.

“His personality is his best friend, but it’s also his worst enemy,” says Immelman.

Still, the loudmouth from Queens has a vulnerable side. He revealed it in a movie review, of all things, with filmmaker Errol Morris in 2002.

Talking about “Citizen Kane,” his favorite movie, Trump spoke with unusual introspection about the accumulation of wealth.

“You learn in Kane that maybe wealth isn’t everything, because he had the wealth but he didn’t have the happiness,” said Trump, who once wanted to become a filmmaker himself.

“In real life, I believe that wealth does in fact isolate you from other people,” he said. “It’s a protective mechanism — you have your guard up much more so than you would if you didn’t have wealth.”

There’s a wariness to the say-anything Trump that has been long in the making.

Trump, in a 1990 Playboy interview, said the loss of his older brother Fred Jr., an alcoholic who died at age 42, “affected everything.”

“He was the first Trump boy out there, and I subconsciously watched his moves,” Trump said. “I saw people really taking advantage of Fred and the lesson I learned was always to keep up my guard 100 percent.” He said he’s a “very untrusting guy.”

The man who has married three times, lives large and offers the opulence of his real estate developments as a metaphor for what he can do for America. But in fact he has relatively simple tastes, if you are to believe him and his family.

He’s never had a drink, smoked or done drugs, he says. He’s a self-proclaimed “germ freak” who’d really rather not shake your hand.

Give him spaghetti and meatballs over pate any day, his sister says.

Or even meatloaf, a Trump favorite when he’s at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, Florida.

“Whenever we have it, half the people order it,” Trump said in a 1997 New Yorker profile. “But then afterward, if you ask them what they ate, they always deny it.”

That, in itself, could be a metaphor for Trump’s success over 16 Republican primary rivals. He appealed to the everyman tired of speechifying pate from political elites and hungry for red meat. (Even if some of his supporters don’t want to admit it.)

Trump’s challenge now is to balance his raging-bull persona with the policy details and presence that voters associate with a president.

In the primaries, says Renshon, Trump “was the guy who had his finger on what people wanted.”

Renshon adds: “The traits that got him to where he has gotten are not necessarily the only traits he’s going to need to get across the finish line.”

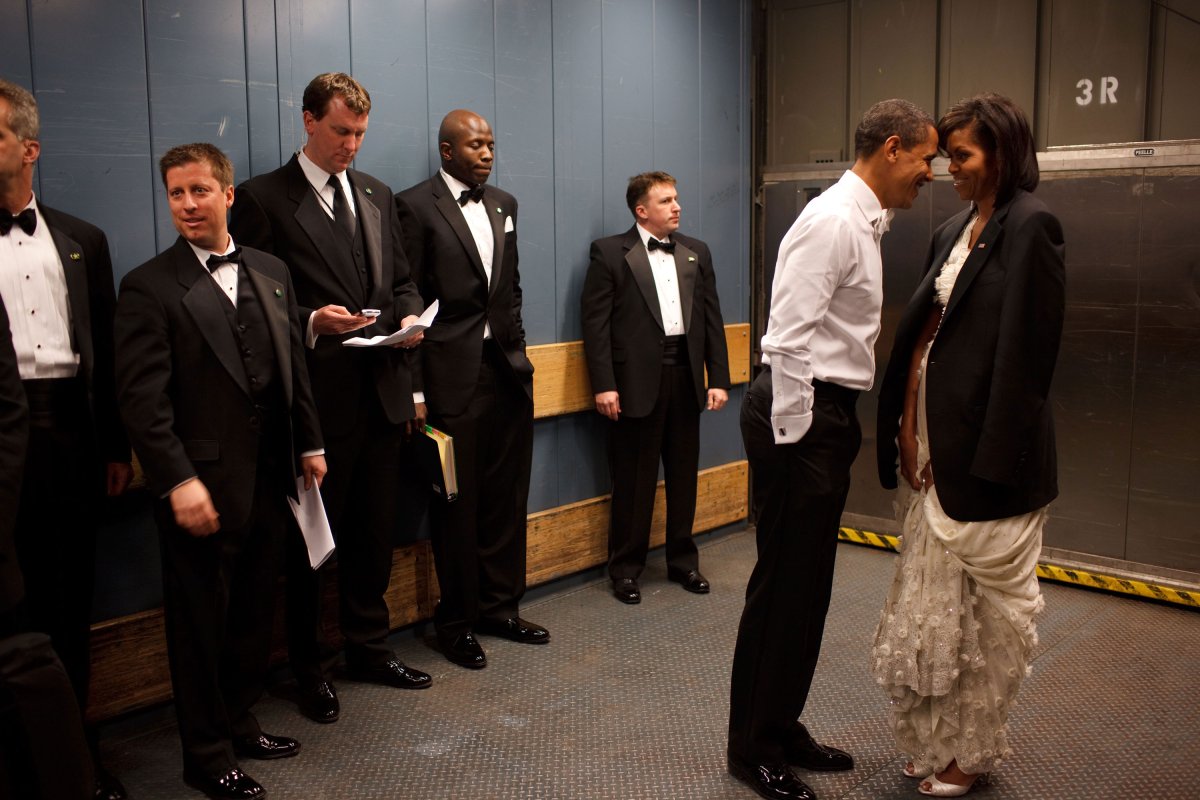

From Agencies, Feature image courtesy AP