Despite almost trebling in the decade ending 2010—from 5.2% to 13.8%—the rate of Muslim enrolment in higher education trailed the national figure of 23.6%, other backward classes (22.1%) and scheduled castes (18.5%). Scheduled tribes lagged Muslims by 0.5%.

The rate of enrolment is described as the percentage of actual enrolments in higher education, regardless of age, in a given academic year, to the 18- to 23-year-old population eligible for higher education in that year according to an article by Indiaspend.

In proportion to their population, Muslims were worse-off than scheduled castes (SCs) and scheduled tribes (STs). Muslims comprise 14% of India’s population but account for 4.4% of students enrolled in higher education, according to the 2014-15 All India Survey on Higher Education.

The situation has worsened over the last half century, according to the 2006 Sachar Committee, appointed to examine the social, economic and educational status of the Muslim community.

In younger SC/STs (aged 20 to 30), the committee reported three times the proportion of graduates as in older SC/STs (aged 51 years and above). Among Muslims, the committee found double the proportion of graduates among younger Muslims compared to older Muslims, “a widening gap between Muslim men and women compared with ‘All Others’, and an almost certain possibility that Muslims will fall far behind even the SCs/STs, if the trend is not reversed”.

Since Justice Rajindar Sachar completed his report a decade ago, the gross enrolment rate of Muslims doubled from 6.84% to 13.8%. Despite this, they trail the national average, as we said.

The 147% increase in SC and 96% increase in ST higher-education enrolments—which still lags their proportion in the general population—since 2001 is the outcome of affirmative action, as we explained in part one of this series. The second part described how the proportion of other backward classes (OBCs) in higher education is now almost the same as their corresponding share of the general population.

So, should reservation be extended to Muslims?

That is not an easy question to answer. In a nation declared secular by its Constitution, educational institutions are disallowed from discriminating between students on religious grounds. However, states can tweak constitutionally-mandated reservation provisions to provide “for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the scheduled castes and the scheduled tribes”.

Where such reservations have been made for Muslims over and above the few Muslim castes included in the OBC list, such as in Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, their representation in higher education is three times the rate in non-minority institutions up North, according to Indian Muslims and Higher Education: A Study of Select Universities in North and South India, a 2013 comparative analysis.

Affirmative action has allowed many families to see their first-generation of graduates, post-graduates and doctorates. It has spurred progressive families to widen their horizons.

“I am the first girl in my family to study journalism, something our elders consider a step forward in career choice for girls,” said Rukku Sumayya, 23, one of two Muslims occupying reserved seats in the post-graduate journalism class of Kerala University.

Read the article here

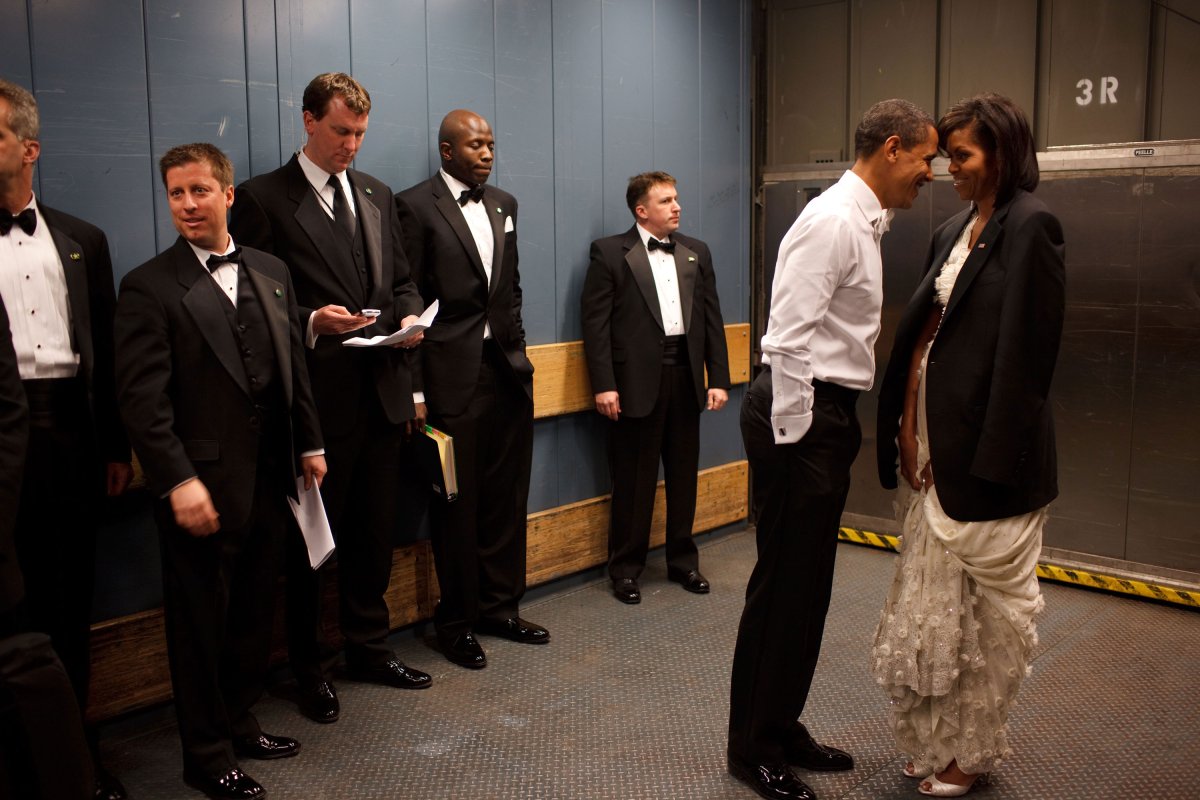

Feature image courtesy livemint