China’s best-known liberal journal has endured, by its publisher’s count, 16 major clashes with authorities since its founding in 1991. It has irritated, and outlasted, two Chinese leaders, he says, but it likely won’t survive President Xi Jinping.

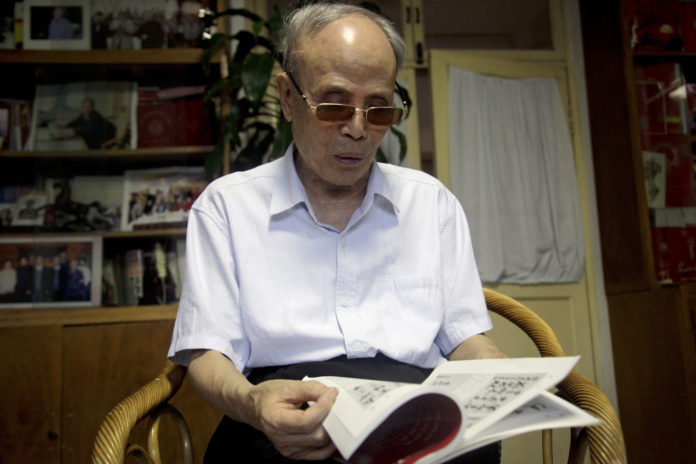

Du Daozheng, publisher of Yanhuang Chunqiu and a stalwart of the Communist Party’s liberal wing, announced this week that the magazine had been suspended. Earlier, government officials replaced the 93-year-old Du, saying he was due for retirement, and seized the magazine’s offices and servers.

Analysts say the effective shuttering of the magazine shows that Xi’s administration is quashing dissent by going to lengths not seen in decades. Yanhuang Chunqiu, which drew a following by exploring sensitive historical subjects, was run and protected by powerful reform-minded officials and intellectuals within the Communist Party itself.

Although the magazine’s former staffers filed a lawsuit last week to regain control, Du said he announced the publication’s suspension because he feared new issues would go out to its 190,000 subscribers under government control without his approval. He struck a weary note as he considered the likelihood of taking back the magazine.

“I don’t think we will pass this final obstacle,” Du said in an interview this week at his Beijing home. “In 25 years we’ve had differences and clashes with authorities, but we’ve always scraped by. Both sides talked and made earnest concessions.

“This time it feels very different. It feels disrespectful of law. It feels crude. It feels violent.”

In a notice posted on the magazine’s website July 15, the Chinese National Academy of Arts, under the Ministry of Culture, said Du had been replaced under a loosely enforced regulation on officials serving into old age. The order came while Du was in the hospital suffering from high blood pressure following his wife’s death.

The ministry did not immediately respond to a faxed request for comment Wednesday.

Senior editors have pledged not to abandon the publication altogether. Still, party members and political observers say the magazine’s likely closure marks the end of an era. While it lasted, the magazine served as a unifying force for liberals, they say.

“The reform-minded factions of the party have always converged under this magazine’s banner,” said Feng Chongyi, a professor in China studies at the University of Technology in Sydney. “It was their platform, perhaps their only platform in mainland China.”

Du is among the last of a generation whose inclinations toward gradual, mild political reforms were bolstered by their revolutionary credentials.

He joined the Communist Party at 14, worked as a reporter for the official Xinhua News Agency and served in the 1980s as head of the state press and publications administration, or China’s top censor. He was an aide to Communist Party leader Zhao Ziyang, and was ousted with Zhao amid the 1989 crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square in Beijing,

Du founded the magazine with support from Xiao Ke, a former vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, and other top-ranking party officials who identified themselves with Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening movement and longed for greater political openness. The journal was known for its commitment to political and economic liberalization and unvarnished historical analyses.

Feng said the magazine’s approach to examining history was not in line with Xi’s emphasis on adhering to the party’s official history, and that Xi’s resolve is such that even someone with Du’s connections and stature had “hit a dead end.”

“They mostly wanted to examine history, the good and the bad,” Feng said. “That to Xi is a distraction that he can’t tolerate, and he’s not scared to move because he is not scared of his elders.”

Hours after being released from the hospital, Du took sympathetic calls at home. He flipped through two tattered notebooks containing the phone numbers of thousands of family friends, party luminaries and the magazine’s numerous supporters, many of whom have passed away.

The old guard’s influence has waned considerably, Du said. He reminisced about when he and his close friend Li Rui, Mao Zedong’s former secretary, could write letters that reached top leaders.

“Why can’t they stand even the advice and grumblings of old cadres?” Du said. “These few years, our freedoms have regressed. We’ve regressed compared to previous leaders. To run counter to the current of the times … is dangerous.”

On an afternoon this week the magazine’s editorial offices were locked and its building empty except for two people who sat in a reception area. A woman who identified herself as a Ministry of Culture employee said she could not answer questions, then closed the door.

Although staffers could not work, top editors have pledged to try to resume normal operations at another location, said deputy editor Wang Yanjun, speaking by telephone from home.

He spoke optimistically about the lawsuit, saying: “We place more trust in Xi’s vow to govern the country according to law.”

Du emphasized that he and the magazine’s supporters are party members and patriots first and foremost. Under a picture of Mao and former Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai on his bookshelf were placed awards he won for participation in the war against the Japanese, and a copy of the July issue that will likely be Yanhuang Chunqiu’s last.

In the issue was calligraphy by Xi Zhongxun, the reform-minded father of the current president, who in his late years praised Du’s magazine as “pretty decent” and urged Du to mentor his son, then a young city official in Hebei province, if the opportunity came.

“I never did,” Du said with faint irony.

“We’ve had a lot of high-level official support, and the size of our subscription base shows how many people think we represent the right direction for the country,” he said. “As an old Communist Party member, I’ve done my duty to my conscience. For that, I have no regrets.”

From Agencies, Feature image courtesy AP