The Pentagon has revised its Law of War guidelines to remove wording that could permit U.S. military commanders to treat war correspondents as “unprivileged belligerents” if they think the journalists are sympathizing or cooperating with enemy forces.

The amended manual, published on Friday, also drops wording that equated journalism with spying.

These and other changes were made in response to complaints by news organizations, including The Associated Press, which expressed concern to Defense Department lawyers and other officials that updates to the manual published last summer contained vaguely worded provisions that commanders could interpret as allowing them to detain journalists for any number of perceived offenses.

“The manual was restructured to make it more clear and up front that journalists are civilians and are to be protected as such,” Charles A. Allen, the Pentagon’s deputy general counsel, said in a conference call with reporters Thursday.

The revised manual more explicitly states that engaging in journalism does not constitute taking a direct part in hostilities.

“Where possible, efforts should be made to distinguish between the activities of journalists and the activities of enemy forces, so that journalists’ activities (such as) meetings or other contacts with enemy personnel for journalistic purposes do not result in a mistaken conclusion that a journalist is part of enemy forces,” the revised manual says.

Jennifer O’Connor, the Pentagon’s top lawyer, said in a statement that consultations with news organizations over the past year “helped us improve the manual and communicate more clearly the department’s support for the protection of journalists under the law of war.”

“It is always a challenge for journalists to work in war zones, but it is particularly tricky when embedding with military forces because the missions are different,” said Kathleen Carroll, executive editor of the AP. “It is important that the Law of War manual recognize that the roles each are different — each important but distinctly different.”

The manual’s earlier version, published in 2015, said that while journalists “in general” are civilians, they “may be members of the armed forces, persons authorized to accompany the armed forces, or unprivileged belligerents.” In the view of experts in military law and journalism, that wording could be interpreted as allowing commanders to detain journalists for perceived offenses.

A person deemed to be an “unprivileged belligerent” is not entitled to the rights afforded by the Geneva Conventions, so a commander could restrict such a reporter from certain coverage areas or even hold the reporter indefinitely without charges.

Pentagon officials had said the 2015 manual’s reference to “unprivileged belligerents” was intended to point out that terrorists or spies could be masquerading as reporters. The revised version makes this explicit by citing the example of “non-state armed groups,” of which al-Qaida would be an example, that use members for propaganda or other media activities, such as those who work for al-Qaida’s Inspire magazine to encourage or recruit militants to join their cause.

The new manual also says journalists should not take action “adversely affecting their status as civilians” if they want to retain protection as a civilian. “For example, relaying target coordinates with the specific purpose of directing an artillery strike against opposing forces would constitute taking a direct part in hostilities,” it says, and in such a case the person would forfeit protection.

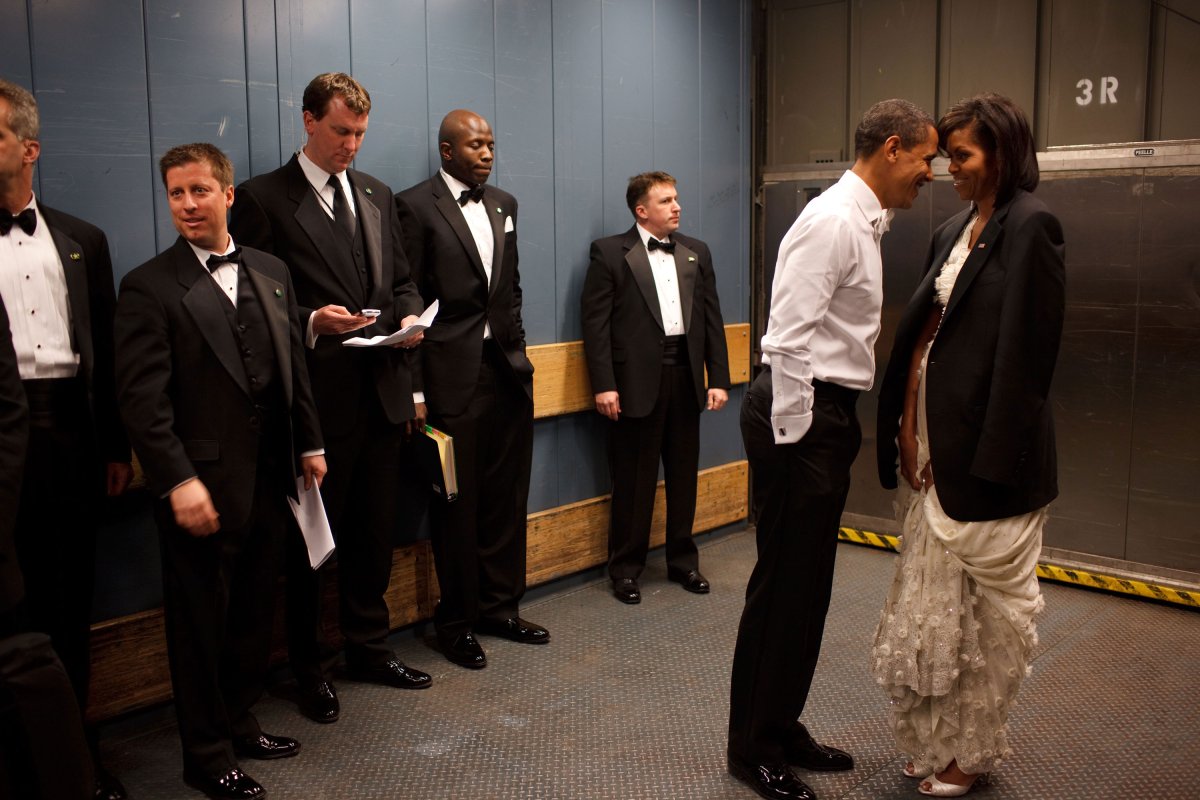

From Agencies, Feature image courtesy AP